How Can Africa Facilitate SPS Investment and Improve Outcomes for Food Safety?

By Getaw Tadesse and Fatima Olanike Kareem

29/03/2023

Photo Credit: USAID/AgriFUTURO

Part I

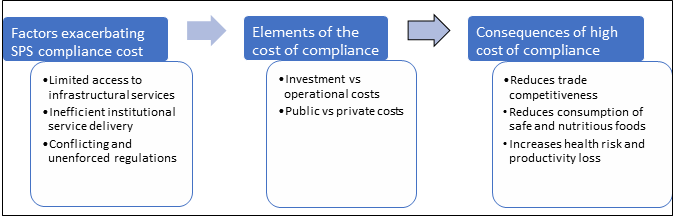

Complying with international sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) standards has become critical to trade and healthy food systems. The World Trade Organization (WTO) allows governments to use SPS measures to protect human, animal and plant health, provided that such measures do not act as a form of disguised protectionism or discrimination against other Member States. However, available evidence suggests that compliance with SPS measures is expensive and complex, with significant adverse effects on both public and private sectors (Figure 1). AKADEMIYA2063, in collaboration with the United States Department of Agriculture-Foreign Agricultural Service (USDA-FAS) with funding from USAID, will explore the costs of SPS compliance and propose solutions to improve trade and food safety.

Consequences and Drivers of SPS Compliance Cost

As the most prevalent non-tariff measures on Africa’s agricultural exports, SPS measures impact trade more significantly than the others. A study in 2018 shows that on average, a ten-percent rise in the number of products affected by SPS measures reduces Africa’s agricultural exports by about 3 percent. Furthermore, when farmers and exporters cannot afford to comply with SPS regulations, the production and consumption of unsafe food persists or increases in the less-regulated African markets. Food-borne illness has reduced productivity by 95 billion USD per year in low- and middle-income countries. However, the trade and health consequences depend on the cost of SPS compliance, which is very much related to access to infrastructure, institutional support and the enforcement of regulatory measures associated with food safety and plant and animal health (Figure 1).

Who Bears the Cost of Compliance?

Available evidence shows that the costs of compliance averages 7.65 percent of total firm sales in sub-Saharan Africa but can reach up to about 124 percent. This figure is astonishing compared to other regions across the world, most of which had average costs of less than half of Africa’s.

When national investment in food safety is low, the costs of compliance can fall disproportionately on exporters, which can lead to bad outcomes. For example, in the late 1990s, Nile perch fish sourced from Lake Victoria posed a huge sanitary concern that caused the outbreak of foodborne diseases. Between 1996 and 2000, the European Union (EU) banned imports of Nile perch and other fish categories, with adverse impacts mainly in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. One such ban was imposed on these countries in April 1999 due to the detection of pesticide fish poisoning in Uganda and was not lifted until December 2000 in Kenya. These rejections spurred governments to revamp SPS investments along the fish supply chain systems and upgrade facilities. For instance, Kenya upgraded facilities and implemented Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) standards. Research suggests that Kenya invested 557,000 USD, amounting to an average cost of 40,000 USD per plant, to address the Nile perch supply chain’s food safety concerns. By the 2000s, this investment had led to an increase in Kenya’s fish exports as the full burden of the cost of compliance no longer fell on exporters. The case of Kenya’s fish exports shows that it’s possible to improve safety and achieve export success.

What Should Be Done?

Even when SPS Measures are not intended to disrupt trade, the high cost of compliance can make it difficult for low- and middle-income countries to maintain their export markets. Specific costs vary widely, especially if they fall disproportionately on any one stakeholder. When costs become too high, both food safety and trade suffer.

Return next week to read Part II, which examines what can be done about the high cost of complying with SPS Standards in Africa.

First published on Agrilinks